Medical Treatments

The most common treatment for TCC are medical treatments (drug therapies). Many drugs can be beneficial, but there is not one drug that stands alone from another. According to Dr. Knapp, at Purdue University, “dogs who live the longest are those that receive more than one treatment protocol (one after the other switching therapies when the cancer begins to grow) during the course of the cancer”(1).

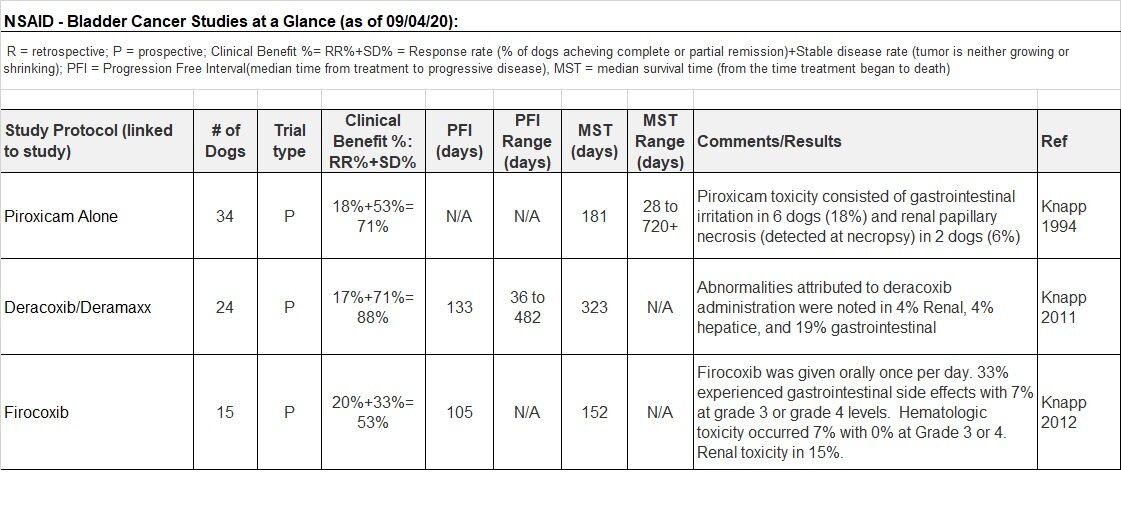

NSAIDS

Cox Inhibitors are often the first line of treatment for TCC. Some pets will experience side effects. A different NSAID should be tried to reduce side effects.IV Chemotherapy

Intravenous Chemotherapy drugs can cause a positive clinical response by shrinking the tumor (remission) or stabilizing the growth of the tumor.Oral Chemotherapy

Some pets are not good candidates for IV Chemotherapy due to stress levels, time commitments, or costs. Oral Chemotherapy is an option.Targeted Therapy

Targeted chemotherapy allows the selective delivery of cytotoxic drugs to tumor cells while limiting the exposure and toxicity to normal tissues.NSAIDS

NSAIDS, such as Piroxicam, Deracoxib, Firocoxib, Carprofen, Meloxicam are anti-inflammatory drugs frequently used to treat pain in dogs, but they also have anti-tumor activity. Here is a great article illustrating the toxicity associated with NSAIDs (2).

Piroxicam

Piroxicam, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is typically a “first line” treatment for TCC in dogs and cats. It has been studied at length for treating TCC, alone and in combination with other chemotherapies. According to Carolyn Henry, from the University of Missouri-Columbia, “because piroxicam is a non-selective cylco-oxygenase (COX) inhibitor, it inhibits both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. Thus, side effects may include gastrointestinal (GI) irritation and nephrotoxicity”(3).

In a study from 1994, 34 dogs with TCC were treated with Piroxicam. 18% of the dogs suffered from GI irritation and 6% suffered from a kidney disorder. 18% of the dogs experienced either complete or partial remission and 53% had stable disease. The median survival time was 181 days, but the range of survival times was from 28 to 720+ days (4). Side effects were managed in this trial.

In a study from 2016, “if gastrointestinal upset occurred that was attributed to piroxicam, piroxicam was withdrawn for 3–5 days (or until clinical signs resolved), and then a selective COX-2 inhibitor, deracoxib (Deramaxx, Novartis, Greensborough, NC; 3 mg/kg daily), was substituted for piroxicam. If worsening azotemia occurred that was considered unrelated to the cancer or secondary urinary tract infection, and possibly due to piroxicam, then piroxicam was stopped, and deracoxib instituted 3–5 days later”(5).

Deracoxib

Deracoxib (Deramaxx) is considered a cox-2 selective inhibitor and is thought to have lower risk of GI ulceration as compared to nonselective NSAIDs like Piroxicam (2). This study from 2011, looked at the antitumor effect and side effects using Deracoxib in 26 dogs with TCC. 17% of the dogs experienced partial remission and 71% had stable disease with median survival time of 323 days (7).

Firocoxib

Firocoxib (Previcox) is another cox-2 selective inhibitor like Deracoxib that is also thought to have lower risk of GI ulceration and bleeding compared to nonselective NSAIDS like Piroxicam (2). This study from 2012, looked at Firocoxib alone and with Cisplatin (chemotherapy drug) in dogs with TCC. When using Firocoxib alone, it induced partial remission in 20% of the 15 study participants and stable disease in 33% of the participants with median survival time of 152 days (9).

Firocoxib provided better pain control in studying arthritic dogs in two different studies when compared to Deracoxib (Deramaxx) (30) and Carprofen (Rimadyl) (31).

Carprofen and Meloxicam

Carprofen (Rimadyl) and Meloxicam (Metacam) are cox-2 preferential agents that appear to have reduced risk of bleeding when compared to nonselective NSAIDs (2). No studies have looked at determining if Carprofen or Meloxicam have antitumor effects with TCC in dogs.

Stomach Protectants for NSAIDs

The use of stomach protectants such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and sucralfate is commonly prescribed with long term use of NSAIDs. According to this study, PPIs have a low risk of side effects, but they do happen (10). The veterinary community still does not have agreement with the science of using a stomach protectant with NSAIDs (11). Some of the newer studies in humans taking NSAIDs long term are showing that taking PPIs along with NSAIDs protects the upper GI tract, but can cause lesions/ulcerations in the lower intestine. This is why some veterinarians do not recommend taking a PPI with long term use of NSAIDs. Probiotics may be helpful in reducing injuries to the lower intestine while taking NSAIDs (12).

A new study in dogs with cancer, from Purdue College of Veterinary Medicine, also finds that PPI’s should not be prescribed as a stomach protectant with Piroxicam/NSAIDs as they found it created more frequent and severe GI adverse events (32).

The links to the actual studies are located in the description of each individual NSAID above this summary in blue text.

Intravenous (IV) Chemotherapy

A summary of the Intravenous Chemotherapy studies is provided in a grid format with links to each study.

Vinblastine

At Purdue’s Bladder Cancer Clinic, Vinblastine along with oral Piroxicam is typically their first line chemotherapy choice for TCC (1). It is given every two weeks. In 2016, a randomized trial was published and dogs treated with vinblastine alone had the following tumor responses: 22% partial remission, 70% stable disease, and 4% progressive disease, and 4% were not able to be evaluated for tumor response. They also discovered, dogs receiving vinblastine and piroxicam together had the following tumor responses: 58% partial remission, 33% stable disease, and 8% progressive disease with a median survival of 299 days (range 21-637 days). An interesting result in this study was the overall median survival time was significantly longer in dogs receiving vinblastine alone followed by piroxicam alone (531 days) than in dogs receiving the combination (299 days) (13). Vinblastine is generally well-tolerated with severe side effects being uncommon (1).

An older study, from 2011, also looked at using Vinblastine in dogs with TCC with slightly worse results. The starting dosage was different from the 2016 study (3.0 mg/m2 vs 2.5 mg/m2). Tumor responses included 10 (36%) partial remission, 14 (50%) stable disease, and 4 (14%) progressive disease. The median progression free interval was 122 days (range, 28–399 days). The median survival time was 147 days (range, 28–476 days) from 1st vinblastine treatment to death and 299 days (range, 43–921 days) from diagnosis to death. The majority of dogs (27 of 28) did not have clinically relevant adverse effects. Seventeen of 28 (61%) dogs required dosage reductions because of neutropenia (14).

In 2016, a study was conducted combining intravenous Vinblastine with oral Toceranib(Palladia). Vinblastine was given every two weeks and Toceranib was given orally Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Per the study, this combination did not result in improved response rates (15).

Mitoxantrone

Mitoxantrone is the second line chemotherapy choice for TCC at Purdue’s Bladder Cancer Clinic if Vinblastine does not work or stops working (1). It is given every three weeks. In 2003, a one-armed prospective trial looked at Mitoxantrone with Piroxicam in dogs with TCC. 35% of the dogs responded with partial remission and 46% with stable disease. The progression free interval was a median of 194 days (range, 0-460 days) and median survival time was 350 days (range,10-675 days) (16).

A newer study in 2015, also looked at Mitoxantrone with Piroxicam in dogs with TCC. 8% achieved partial remission and 69% achieved stable disease. This study discusses some possible reasons for the different results compared to the 2003 study. The progression free interval was a median of 106 days (range, 21-383 days) and median survival time was 249 days (range, unknown) (17).

Carboplatin

Carboplatin is the third line chemotherapy choice for TCC at Purdue’s Bladder Cancer Clinic if Vinblastine and Mitoxantrone do not work or have stopped working (1). Based on the studies, it appears to have more side effects than Vinblastine or Mitoxantrone. It is given every 3 weeks.

A 2005 study conducted by Dr. Knapp at Purdue, looking at the combination of Carboplatin with Piroxicam showed results of 38% partial remission and 45% stable disease with a median survival time of 161 days. GI toxicity occurred in 74% of the dogs and hematologic toxicity in 35% of the dogs ranging from mild to severe (18).

A more recent study from 2015 had different results. This study looked at the combination of Carboplatin with Piroxicam but had a 13% response rate and 54% stable disease with a progressing free interval of 74 days (range, 13 to 548 days) and median survival time of 263 days. GI toxicity occurred in 26% of the dogs. 13% of the dogs required dose reductions. This study discusses the potential reasons for the difference in outcomes compared to the 2005 study. They hypothesize that the response rate differences could be due to the technology used to measure the tumor size. The GI toxicity is much lower in this study, the study thinks it might be due to 17% of the dogs had their treatment every 4 weeks instead of every 3 weeks due to low blood counts (17).

Another study in 2015, compared intravenous Carboplatin with intraarterial Carboplatin along with NSAIDs in treating TCC. This study focused solely on tumor response and not survival times or progression free intervals. The intraarterial Carboplatin with intraarterial Meloxicam given only twice, three weeks apart, produced a partial response in 36% and stable disease in 64% of the dogs. These measurements were taken within three weeks from the first treatment, where the other studies were taken over a longer time frame. The side effects in the intraarterial group were less than the intravenous group but there were some procedural complications (9% during and 9% post procedure) (19).

Cisplatin

Another chemotherapy drug sometimes used to treat TCC is Cisplatin. Based on the studies, it appears to have higher side effects than other drugs. It is given every 3 weeks. In a study conducted by Dr. Knapp at Purdue in 2000, Cisplatin alone followed by Piroxicam when Cisplatin stopped working was compared with the combination of Cisplatin with daily Piroxicam. Tumor measurement was obtained after two treatments were given. The Cisplatin alone group resulted in 50% of the dogs achieving stable disease, 84 day (range, 42-151 days) progression free interval and a median survival time of 309 days (range, 140 - 518 days) (including once Piroxicam was given when Cisplatin was discontinued). Renal toxicity was reported in 50% of the dogs. Hematologic toxicity occurred in 36%. Gastrointestinal toxicity occurred in 38%.

The other arm of this study, combining Cisplatin along with daily oral Piroxicam resulted in 71% response rate including 14% with complete remissions, and the remaining 29% with stable disease. This means 100% of the study population had a clinical benefit with this treatment. The progression free interval was 124 days (range, 46 - 259 days) and the median survival time was 246 days (range, 46 - 810 days). Renal toxicity was reported in 86% of the dogs. Hematologic toxicity occurred in 36%. Gastrointestinal toxicity occurred between 50% and 65% but were generally mild (20). Notice the median survival time was higher in the Cisplatin followed by Piroxicam arm of the trial (309 days vs 246 days).

Another study by Dr. Knapp at Purdue in 2012, looked at Cisplatin alone compared to Cisplatin combined with Firocoxib (Previcox). Cisplatin was given every 3 weeks. The Cisplatin alone resulted in a response rate of 13% and stable disease of 53%. The progression free interval was 87 days and median survival time was 338 days. These results are similar to the 2000 study of Cisplatin alone. Toxicity remained high with 93% experienced gastrointestinal side effects with 40% at grade 3 or grade 4 levels. Hematologic toxicity occurred 60% with 20% at Grade 3 or 4. Renal toxicity in 33% (9).

The other arm of this study, combining Cisplatin along with daily Firocoxib resulted in 57% response rate and 21% stable disease. The progression free interval was 186 days and median survival time was 179 days. 66% experienced gastrointestinal side effects with 58% at grade 3 or grade 4 levels. Hematologic toxicity occurred 36% with 0% at Grade 3 or 4. Renal toxicity in 45% (9). Again, toxicity remained high.

Gemcitabine or Doxorubicin

Two other chemotherapy drugs used in treating TCC are Gemcitabine and Doxorubicin. In a study from 2011, Gemcitabine with Piroxicam were studied and resulted in a 26% response rate and 50% stable disease. The median survival time was 230 days. 68% had gastrointestinal toxicity (Grade 1-3) and 26% had neutropenia toxicity (Grade 1-3). All dogs had improvement in clinical signs (21).

In a study from 2013, Doxorubicin with Piroxicam were studied and resulted in a 9% response rate and 61% stable disease. The progression free interval was 103 days and the median survival time was 168 days. Gastrointestinal toxicity was generally mild (22).

Here is a summary of the IV Chemotherapy studies discussed above in a grid format with the links to the actual studies. Please remember, there is a lot of detail in the individual studies that can impact the outcomes of the individual drug. Do not judge a drug based solely on any individual measurement. Use this information to facilitate your discussions with your pet’s oncologist or veterinarian.

Oral “Metronomic” Chemotherapy

Metronomic refers to frequent (normally daily), low dose, oral administration of chemotherapy. The dosage is low for it to be given daily. The goal of this type of treatment is not to kill the cancer, but to stop the formation of new blood vessels in the cancer. The expected outcome of metronomic chemotherapy is that the cancer will stop growing for a period of time (ideally for many months or more). The cancer is not expected to shrink, but to stabilize in growth (1). Here is a good general article “FAQ About Metronomic Chemotherapy”(29).

Lapatinib

This new study from 2022 from the University of Tokyo, described the use of lapatinib as a first-line treatment option for dogs with muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. 44 dogs were assigned to the Lapatinib/Piroxicam group versus 42 dogs in the Piroxicam only group. The clinical response was better in the Lapatanib/Piroxican group with 2% complete remission, 52% partial response, 34% stable disease, and 12% progressive disease. In the Piroxicam only group, 9% partial remission, 67% stable disease, and 34% progressive disease. The median progression free survival (PFS) in the combination Lapatinib/Piroxicam group was 193 days with a range of 28-560 days compared to 90 days with a range of 21-318 days in the Piroxicam only group. Overall median survival (OS) in dogs treated with lapatinib/piroxicam were 435 (range 65–1023) days and dogs treated with piroxicam alone were 216 (range 41–725) days, The study also showed a greater clinical response to lapatinib treatment and significant increase in PFS and OS in dogs with HER2 overexpression than in those with low HER2 expression.(35)

Adverse Events: Of the 44 dogs with lapatinib/piroxicam, 36 (82%) had an adverse event. Most treatment-related adverse events were grade 1 or 2, and many were transient. The leading adverse events were increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP; 48%), increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 45%), vomiting (18%), diarrhea (18%), anorexia (11%), increased total bilirubin (11%), and increased creatinine (11%). There were no grade 4–5 treatment-related adverse events. Although no dog exhibited an event leading to discontinuation, the lapatinib dose was reduced in four dogs (9%). Of the 42 dogs treated with piroxicam alone, 17 (40%) had an adverse event. The leading adverse events were increased creatinine (17%), anorexia (14%), increased ALP (12%), and vomiting (10%).(35)

This drug is an available treatment option through FidoCure.

Chlorambucil

In this study from 2013, Dr. Knapp and the team from Purdue, studied the effect of Chlorambucil on 31 dogs with TCC. 29 of these dogs had failed other prior treatments. The results were 3% experienced partial remission and 67% experienced stable disease. The median progression free interval was 119 days (range, 7 - 728 days) and the median survival time was 221 days (range, 7 -747 days). Only 7 dogs (23%) had side effects which were typically mild. Only 1 dog (3%) had a grade 3 toxicosis, and that was not detected until 20 months after chlorambucil treatment was started. Chronic suppression of bone marrow can occur with long term treatment (1, 23).

Palladia

This study from 2019, retrospectively reviewed treating 37 dogs diagnosed with bladder tumors with Palladia (Toceranib Phosphate). 34 of the 37 dogs were treated on average with 2 prior chemotherapy drugs. The results were 7% experienced partial remission and 80% experienced stable disease. The median progression free interval was 96 days (range, 30-599 days) and the median survival time was 149 days (range, 5-710 days). All dogs had at least one adverse event, but most were transient and mild (grades 1 and 2). 56% of dogs had progression of azotemia (excess of nitrogen in the blood which could lead to kidney failure) while receiving Palladia (24).

Note: please contact me if you want to see the full study instead of the abstract, I purchased it and am not allowed by the publisher to publish it on this site.

Paclitaxel

The use of Paclitaxel has not been frequently used in veterinary medicine due to the high prevalence of acute hypersensitivity reactions to conventional Cremophor®EL added drugs. To overcome this difficulty substances that do not cause hypersensitivity reactions when added to paclitaxel have been developed for safe drug delivery. This study from 2022, was designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral paclitaxel (DHP107-VP) in dogs with various cancers including 5 dogs with TCC. 4 of the 5 dogs (80%) were able to achieve stable disease with a median overall survival of 284.5 days with a range of 71-824 days. The median progression free survival was 148 days with a range of 22-741 days all co-administered with an NSAID. 38% of all participants had an adverse event which were mostly grade 1-2; Bone marrow suppression developed in 14%, vomiting in 10% and diarrhea in 14% of dogs (33).

Another study from 2020, produced similar results using paclitaxel in treating TCC in dogs (34). Both studies used very small study populations of only 5 dogs per study.

The links to the actual studies are located in the description of each individual oral chem drug above the summary in “blue” text.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted chemotherapy allows the selective delivery of cytotoxic drugs to tumor cells while limiting the exposure and toxicity to normal tissues. The resulting preferential accumulation of drug in the tumor can increase drug activity with lower systemic exposure, i.e. increasing the therapeutic index. Folate receptors (FR) may be of use for targeted delivery of cytotoxic drugs in invasive urothelial carcinoma (iUC) also known as transitional cell carcinoma, for which improved therapy is needed.

Folate Vinblastine

In this study from 2012, folate receptors expression and function in iUC were explored and the antitumor activity and toxicity of a folate-targeted vinblastine conjugate were evaluated in dogs with naturally occurring iUC. Maximum tolerated dosage was defined as 0.25 mg/kg once weekly. No urologic toxicity occurred. In dogs receiving several weeks of treatment, dose reduction did become necessary due to GI toxicity and neutropenia. Neutropenia occurred in 4 dogs receiving a lower dose of EC0905 (grade 1 in 3 dogs and grade 2 in 1 dog). 56% of dogs experienced partial remission and 44% experienced stable disease. The median progression free interval was 58 days (range, 3-428 days) and the median survival time was 115 days (range, 3-428 days) (25).

Folate-Tubulysin

In this study from 2018, Folate-tubulysin was given intravenously every two weeks. The majority of the dogs presented with advanced age, cancer stage, and/or co-morbidities. No dog withdrew from the study due to an adverse event or negative effects towards quality of life. Toxicity noted consisted of neutropenia, anorexia, or lethargy. Clinical benefit was found in 20 of the 28 dogs (71%), including partial remission in three dogs and stable disease in 17 dogs. The median progression free interval for all dogs was 103 days (range 24–649 days) (26).

FidoCure

FidoCure® (part of the One Health Company) has a mission to eradicate cancer in dogs. They use genomic testing (Cadet BRAF urine test) to identify possible cancer-causing mutations and then suggest targeted therapy to attack the cancer cells. FidoCure will work with your veterinarian for a fixed fee and provide oral targeted therapy for TCC using FDA approved human targeted therapies. Unfortunately, they do not provide any research studies on dogs supporting their therapy recommendations for TCC. They will generally recommend the drugs Lapatinib or Trametinib to treat TCC. There is a study for Trametinib but it is with cells, not on real dogs (27). Here is a published adverse event analysis on their targeted therapies (28).

In June 2022, Fidocure published median survival time outcomes for TCC using Lapatinib with Trametinib and chemo of 425.5 days (36). However, the Lapatinib study as a first line treatment with the addition of Piroxicam for TCC had a similar MST of 435 days (35).

References (includes links to source documents):

Knapp, D., 2020. Urinary Bladder Cancer Research. [online] Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. Available at: <https://vet.purdue.edu/pcop/urinary-bladder-cancer-research.php#:~:text=The%20most%20common%20cancer%20of,cells%20that%20line%20the%20bladder.> [Accessed 06 September 2020].

Trepanier, L., 2013. Nsaids: Comparative Toxicity And Drug Interactions - WSAVA2013 - VIN. [online] Vin.com. Available at: <https://www.vin.com/apputil/content/defaultadv1.aspx?pId=11372&catId=35316&id=5709854> [Accessed 6 September 2020].

Henry, C., 2004. Transitional Cell Carcinoma - WSAVA2007 - VIN. [online] Vin.com. Available at: <https://www.vin.com/apputil/content/defaultadv1.aspx?pId=11242&catId=31932&id=3860788> [Accessed 6 September 2020].

Knapp DW, Richardson RC, Chan TC, et al. Piroxicam therapy in 34 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. J Vet Intern Med. 1994;8(4):273-278. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.1994.tb03232.x

Knapp DW, Ruple-Czerniak A, Ramos-Vara JA, Naughton JF, Fulkerson CM, Honkisz SI. A Nonselective Cyclooxygenase Inhibitor Enhances the Activity of Vinblastine in a Naturally-Occurring Canine Model of Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma. Bladder Cancer. 2016;2(2):241-250. Published 2016 Apr 27. doi:10.3233/BLC-150044

Brooks, W., 2003. Piroxicam - Veterinary Partner - VIN. [online] Veterinarypartner.vin.com. Available at: <https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&catId=102894&id=4951987&ind=1497&objTypeID=1007> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

McMillan SK, Boria P, Moore GE, Widmer WR, Bonney PL, Knapp DW. Antitumor effects of deracoxib treatment in 26 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;239(8):1084-1089. doi:10.2460/javma.239.8.1084

Brooks, W., 2003. Deracoxib (Deramaxx) - Veterinary Partner - VIN. [online] Veterinarypartner.vin.com. Available at: <https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4951865> [Accessed 8 September 2020].

Knapp DW, Henry CJ, Widmer WR, et al. Randomized trial of cisplatin versus firocoxib versus cisplatin/firocoxib in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27(1):126-133. doi:10.1111/jvim.12013

Marks SL, Kook PH, Papich MG, Tolbert MK, Willard MD. ACVIM consensus statement: Support for rational administration of gastrointestinal protectants to dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(6):1823-1840. doi:10.1111/jvim.15337

Jones SM, Gaier A, Enomoto H, et al. The effect of combined carprofen and omeprazole administration on gastrointestinal permeability and inflammation in dogs [published online ahead of print, 2020 Sep 7]. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;10.1111/jvim.15897. doi:10.1111/jvim.15897

Gwee KA, Goh V, Lima G, Setia S. Coprescribing proton-pump inhibitors with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: risks versus benefits. J Pain Res. 2018;11:361-374. Published 2018 Feb 14. doi:10.2147/JPR.S156938

Knapp DW, Ruple-Czerniak A, Ramos-Vara JA, Naughton JF, Fulkerson CM, Honkisz SI. A Nonselective Cyclooxygenase Inhibitor Enhances the Activity of Vinblastine in a Naturally-Occurring Canine Model of Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma. Bladder Cancer. 2016;2(2):241-250. Published 2016 Apr 27. doi:10.3233/BLC-150044

Arnold EJ, Childress MO, Fourez LM, et al. Clinical trial of vinblastine in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25(6):1385-1390. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00796.x

Rippy SB, Gardner HL, Nguyen SM, et al. A pilot study of toceranib/vinblastine therapy for canine transitional cell carcinoma [published correction appears in BMC Vet Res. 2016 Dec 30;12 (1):291]. BMC Vet Res. 2016;12(1):257. Published 2016 Nov 17. doi:10.1186/s12917-016-0882-6

Henry CJ, McCaw DL, Turnquist SE, et al. Clinical evaluation of mitoxantrone and piroxicam in a canine model of human invasive urinary bladder carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(2):906-911.

Allstadt SD, Rodriguez CO Jr, Boostrom B, Rebhun RB, Skorupski KA. Randomized phase III trial of piroxicam in combination with mitoxantrone or carboplatin for first-line treatment of urogenital tract transitional cell carcinoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29(1):261-267. doi:10.1111/jvim.12533

Boria PA, Glickman NW, Schmidt BR, et al. Carboplatin and piroxicam therapy in 31 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Vet Comp Oncol. 2005;3(2):73-80. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5810.2005.00070.x

Culp WT, Weisse C, Berent AC, et al. Early tumor response to intraarterial or intravenous administration of carboplatin to treat naturally occurring lower urinary tract carcinoma in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29(3):900-907. doi:10.1111/jvim.12594

Knapp DW, Glickman NW, Widmer WR, et al. Cisplatin versus cisplatin combined with piroxicam in a canine model of human invasive urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;46(3):221-226. doi:10.1007/s002800000147

Marconato L, Zini E, Lindner D, Suslak-Brown L, Nelson V, Jeglum AK. Toxic effects and antitumor response of gemcitabine in combination with piroxicam treatment in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238(8):1004-1010. doi:10.2460/javma.238.8.1004

Robat, C., Burton, J., Thamm, D. and Vail, D. (2013), Retrospective evaluation of doxorubicin–piroxicam combination for the treatment of transitional cell carcinoma in dogs. J Small Anim Pract, 54: 67-74. doi:10.1111/jsap.12009

Schrempp DR, Childress MO, Stewart JC, et al. Metronomic administration of chlorambucil for treatment of dogs with urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013;242(11):1534-1538. doi:10.2460/javma.242.11.1534

Gustafson TL, Biller B. Use of Toceranib Phosphate in the Treatment of Canine Bladder Tumors: 37 Cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2019;55(5):243-248. doi:10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6905

Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, Naughton JF, et al. Targeting folate receptors to treat invasive urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(2):875-884. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2101

Szigetvari NM, Dhawan D, Ramos-Vara JA, et al. Phase I/II clinical trial of the targeted chemotherapeutic drug, folate-tubulysin, in dogs with naturally-occurring invasive urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(97):37042-37053. Published 2018 Dec 11. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.26455

Cronise KE, Hernandez BG, Gustafson DL, Duval DL. Identifying the ErbB/MAPK Signaling Cascade as a Therapeutic Target in Canine Bladder Cancer [published correction appears in Mol Pharmacol. 2020 Jul;98(1):23]. Mol Pharmacol. 2019;96(1):36-46. doi:10.1124/mol.119.115808

Post, G., 2020. Fidocure® Targeted Therapies Early Data Shows Similar Adverse Effects To Palladia. [online] FidoCure Blog. Available at: <https://www.fidocure.com/veterinary-oncology/blog/fidocure-targeted-therapies-early-data-shows-similar-adverse-effects-to-palladia/> [Accessed 16 September 2020].

Ettinger, S., 2019. FAQ About Metronomic Chemotherapy. [online] Drsuecancervet.com. Available at: <https://drsuecancervet.com/wp-content/uploads/veterinary_handout_metronomic_chemo.pdf> [Accessed 11 October 2020].

Ryan, W., 2010. Field Comparison of Canine NSAIDs Firocoxib and Deracoxib.. [online] Jarvm.com. Available at: <https://www.jarvm.com/articles/Vol8Iss2/Vol8%20Iss2Carithers.pdf>.

Hazewinkel HA, van den Brom WE, Theyse LF, Pollmeier M, Hanson PD. Comparison of the effects of firocoxib, carprofen and vedaprofen in a sodium urate crystal induced synovitis model of arthritis in dogs. Res Vet Sci. 2008 Feb;84(1):74-9. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.02.005. Epub 2007 Apr 3. PMID: 17408711.

Shaevitz MH, Moore GE, Fulkerson CM. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trial comparing the incidence and severity of gastrointestinal adverse events in dogs with cancer treated with piroxicam alone or in combination with omeprazole or famotidine. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2021 Aug 15;259(4):385-391. doi: 10.2460/javma.259.4.385. PMID: 34337965.

Chae HK, Oh YI, Park S, An JH, Seo K, Kang K, Chu SN, Youn HY. Retrospective analysis of efficacy and safety of oral paclitaxel for treatment of various cancers in dogs (2017-2021). Vet Med Sci. 2022 May 27. doi: 10.1002/vms3.829. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35633063.

Chae HK, Yang JI, An JH, Lee IH, Son MH, Song WJ, Youn HY. Use of oral paclitaxel for the treatment of bladder tumors in dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 2020 May 30;82(5):527-530. doi: 10.1292/jvms.19-0578. Epub 2020 Apr 3. PMID: 32249251; PMCID: PMC7273596.

Maeda S, Sakai K, Kaji K, Iio A, Nakazawa M, Motegi T, Yonezawa T, Momoi Y. Lapatinib as first-line treatment for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma in dogs. Sci Rep. 2022 Jan 13;12(1):4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-04229-0. PMID: 35027594; PMCID: PMC8758709.

FidoCure, Improving Cancer Patient Outcomes, June 2022 Outcomes Data Compilation, ACVIM22, 2022 June;8.